Introduction

*Scroll to the bottom of the page for recent updates to the study

Dr. Ferguson, drawing on his experience and penchant for exploration, has developed a unique,

simple, and inexpensive way to help some tendons and suspensory ligaments heal in a very

accelerated fashion. The key is to enable the inflammatory fluid that is present with all tendon

and suspensory injuries to escape the tendon. This inflammatory fluid holds destructive enzymes

and acts as a matrix for scar or fibrous tissue, as opposed to the normal tendon tissue, which is

elastic. The procedure has been named “percutaneous decompression”.

From a historical perspective, this concept is not particularly new. Years ago, before ultrasound

helped us better understand the anatomical considerations of bowed tendons, Dr. Ferguson and

others would surgically “split” a damaged tendon with a glorified sharpened screwdriver looking

device (a tendon knife); and a dramatic reduction in size and pain of the bowed tendon would be

manifested immediately. Unfortunately, the crude methodology probably damaged a significant

number of tendon fibers in the process and prognosis for a prolonged recovery was guarded at

best. Another procedure involved puncture of the suspensory ligament in conjunction with

sesamoid fractures and surgery. And recently there has been the introduction of new ultrasonic

devices and sophisticated lasers that aim to force the inflammatory fluid from the damaged

tendons or ligaments.

Of course with the advent of ultrasound we were able to acknowledge the presence of the fluid as

well as specific tendon fiber damage. The prognosis for a return seemed to be directly related to

the percentage of damaged fluid area relative to normal tendon area. Initially, the idea was to

wait for the fluid to “dissipate”; and when this was found to be an ineffective treatment with

some tendons, the next ideas were to inject damaged sites with vague healing agents such as

bone marrow, PRP, and “stem cells.” In Dr. Ferguson’s experience, these agents have not been

effective in significant tendon and suspensory injuries; and just recently saline has been shown

just as effective. Dr. Ferguson, for some time, has used saline injections to stimulate suspensory

ligament branch injuries that were resistant to healing on their own. Nevertheless, he found that

small tendon injuries would heal satisfactorily on their own, and over 95% of suspensory branch

injuries would heal in about 4 months. Larger tendon injuries had a much poorer prognosis.

The Simple Discovery

directly over the proximal portion of the suspensory ligament. As destiny would have it, the

horse was also sore in the suspensory. Dr. Ferguson decided to go ahead and puncture the

suspensory with the acupuncture needle. The resulting suspensory was NOT sore following the

treatment and remained non-painful. That same day, Dr. Ferguson examined another horse that

had a small, but obvious, tendon injury. He punctured this area; and the next week the tendon

was normal and remained normal through training and racing. Multiple tendons were then treated

with large bowed tendons returning to normal size and palpating non-painful in 3-6 treatments

(3-6 weeks). Some treatments were also combined with shockwave therapy to help force fluid

from the tendon space. Two horses raced successfully quite quickly following treatment.

Unfortunately, in the earlier studies ultrasound examinations were conducted infrequently and

horses were in a racetrack setting where continuing to race was paramount to some owners.

Some horses, probably due to returning to racing prematurely, re-injured their tendons after

resuming exercise. It appears that ultrasound verification of healing is extremely important to

success in this procedure. Also, treatment of lower suspensory branch lesions has not been as

successful with percutaneous decompression alone. Adjunct shockwave therapy has been helpful

in accelerating this area’s healing response.

Anatomical Considerations

First the superficial flexor tendon, in the horse, is surrounded by a thick fibrous sheath. This

sheath is not only quite supportive, but also quite restrictive to allowing fluids to transverse it or

even leave the tendon. In a certain number of tendon injuries, especially ones up near the knee,

there may even be lameness associated with the tendon tear due to forces exerted on the sheath.

But generally lameness is not associated with bowed tendons. Same with suspensory lesions;

proximal generally give obvious lameness, low injuries not necessarily. It would also be Dr.

Ferguson’s opinion that there is perhaps less fiber damage in proximal injuries than distal injuries

of both the tendon and suspensories. It is also important to realize that when a horse is fully

weight bearing on a tendon or ligament, extreme forces are exerted on any inflammatory fluid

that has displaced the intact fibers.

Conclusions…Thus Far

- Dramatic recoveries from large bowed tendons can be realized if there is minimal fiber

damage. Perhaps this is more related to more proximal injuries. - Ultrasound should be utilized to assess initial and residual fiber damage. It’s imperative

with tendons that the fibers are allowed enough time (handwalking appears helpful) for

the fibers to heal back to normal alignment. At this time it appears that it takes 4-6 weeks

for a suspensory to heal enough to return to training. This time frame might be

substantially longer for a low suspensory branch lesion near or at the sesamoid

(sesamoiditis). Tendons appear to take 4-6 weeks for the lesion to “fill in”, and another

4-6 weeks for the fibers to realign. (See photos) - Tendons that have sustained a large amount of fiber damage with resulting scar tissue

formation, are almost non-responsive to percutaneous puncture. - Generally, with a low number of cases so far, lower suspensory branch lesions, which

probably mainly consist of damaged fibers, are not that responsive to percutaneous

puncture. Healing usually is decreased from 4 months to 3 months. - Proximal and mid-body suspensory lesions can be dramatically responsive to

percutaneous puncture. - Shockwave therapy appears to be a useful adjunct tool to help drive fluid from the lesion.

Obviously it is optimal to perform such a procedure as close to the decompression as

possible.

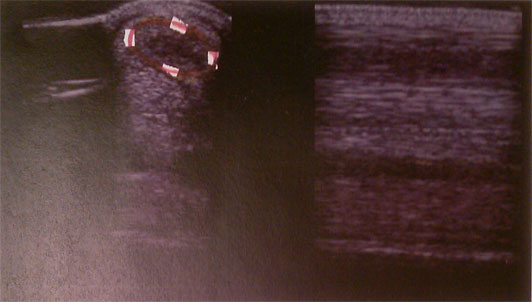

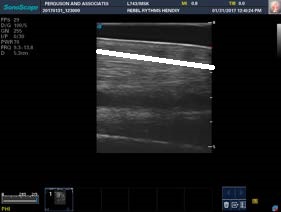

tendon injury, day one

tendon injury, post two treatments (two weeks) NOTE: substantial damaged fibers remain

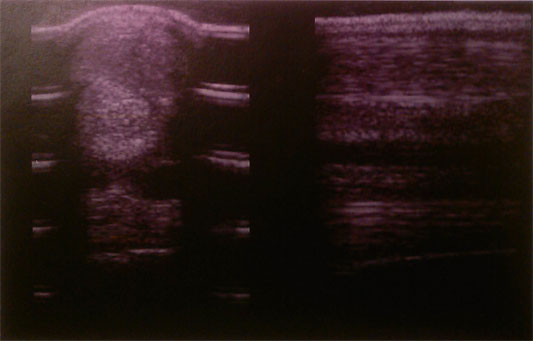

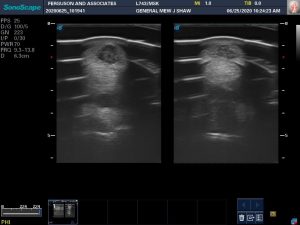

example of a small, but significant, tear in the proximal suspensory

example of a distal suspensory branch lesion

Updated: March 1, 2017

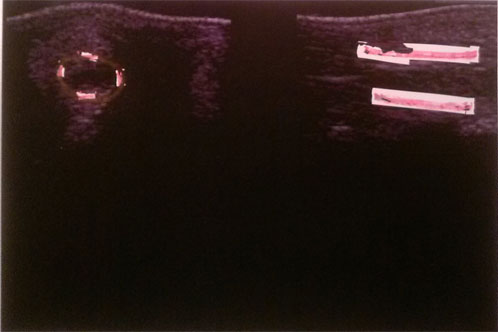

These are 2 pictures of a tendon taken 6 weeks apart. On the picture on the left notice the black hole to the left of the arrow. Black on an ultrasound represents fluid. Notice on the picture on the right, after three treatments of decompression, the fluid is no longer present.

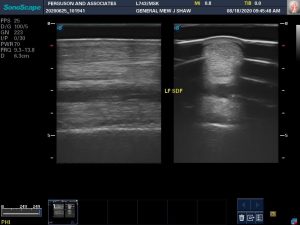

These images are of the same tendon as above but are oriented horizontally. The tendon picture on the right is 6 weeks older than the one on the left. Above the blue line is the area of injury with black representing fluid. The fluid has dissipated on the tendon on the left but on close observation with a capable ultrasound one can ascertain the tendon fibers are not realigned it. This horse will subsequently walk another 4 weeks and then resume normal training contingent on a good scan of fiber alignment, for a total of 10 weeks off for a substantial bowed tendon.

To date, having began doing the procedures in 2013, 138 tendons have been treated, and 137 suspensory ligaments. We are currently assessing statistical race results though most of the horses in the study are juveniles in training and not currently racing at time of treatment.

Updated: August 21, 2020

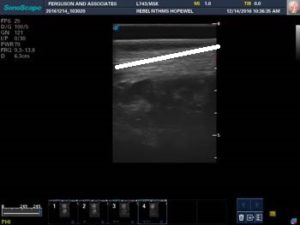

So, as a picture of a typical, but yet very dramatic, representation of the effectiveness of needle tendon puncture, the first image, is one tendon, the left fore, before treatment, which consisted of 4 weekly punctures; and below is the same tendon 7 weeks later. The black hole, mostly inflammatory fluid, is gone. What remains are mal-aligned tendon fibers as seen on the longitudinal scan on the second image. The horse has been strictly stall rested up to this point. Now he can walk, and only walk, with no turn out, until the tendon fibers are normal. This horse has a very large lesion and it will take much longer for his fibers to mature to normal than a small lesion. Yet they do come around.

H.O. Ferguson, DVM